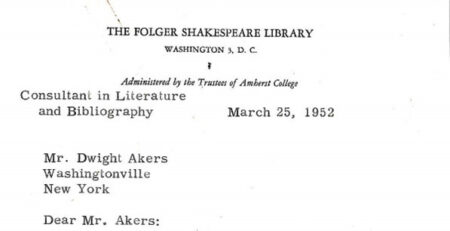

Blooming Grove and the First World War: Part 2

In December 1917, Washingtonville resident Elsa S. Gerow wrote to Private David Wright Hudson, who was going through basic training at Chattanooga Tennessee:

“Do you know we had a small pretty little blizzard Saturday and the mercury still stays near zero. Real winter. Aren’t you glad you are below the blizzard line? Think of the poor fellows guarding the N.Y. Aqueduct. Joy, it must be cold along those hills below New Paltz- Yet those boys are having a quiche compared to those “over there”. [1]

When the United States entered World War One in the Spring of 1917, America’s national security was placed on high alert. Despite declaring neutrality at the outbreak of war three years earlier, American factories and farms had been supplying food and munitions to allied forces fighting on the western front in return for turning a profit. David Hudson’s cousin Emily wrote him in November, 1917:

“James has been drafted, but don’t have any idea they will take him on account that he is working in the ammunition plant. He has been there nearly or quite two years (Bridgeport) – Oliver is there too.” [2]

This put American munitions plants in the cross-hairs of possible German saboteurs seeking revenge on the British naval blockade of German shipping. On July 30th 1916, the Black Tom munitions depot on Black Tom Island, New Jersey was rocked by a massive explosion, leaving three dead, and hundreds of nearby residents severely injured. The implication that German spies were involved in this act led to backlash against German-American immigrants, as well as heightened security for factories and transportation hubs necessary to produce and move materials and men to the front lines [3].

The Hudson Valley would play a major role in supplying the industrial hubs of New York City, and New Jersey with fresh water via the New York Aqueduct, as well as transportation for men and war materials through the many railway lines and bridges that linked New York State to New York City, and Hoboken, New Jersey. Protecting these resources were men from the New York National Guard and provisional New York Guard. Beginning in April, 1917, the 71st Regiment, New York National Guard established a temporary headquarters in Middletown, and posted various companies; groups of soldiers comprising of 150 men, throughout Orange, Sullivan, and Delaware Counties. In our area were located, Company F in Cornwall, the Machine Gun Company at Orr’s Mills, and Company M at Washingtonville. The Machine Gun Company established its camp on the Brown Farm in Salisbury Mills, and protected the Erie trestle from possible sabotage. According to Robert Stewart Sutliffe in his 1922 book “Seventy-First New York in the World War”, the regiment was to guard:

“Railroad bridges, viaducts, munition plants and other property, the destruction or damaging of which would have impeded the operation of the war were under the protection of the 71st” [4]

The photographs of the 71st encampment at Brown farm in the library’s collection shows how locals became wrapped up in the excitement of having the regiment in the area. Ruth and Susan Brown had their portraits taken with a few men of the Machine Gun Company, and another shows them and their friends having a picnic with other soldiers in camp.

During the regiment’s time in the area, soldiers participated in recruitment drives, drill exercises and attempted to root out “Disloyal residents”. On April 7th, 1917 the New York Evening World reported that Colonel William G. Bates, the 71st’s commander, lead a detachment to destroy a “private radio station” after receiving “confidential intelligence of great importance”, along with word of “large quantities of dynamite were stored in houses of two Germans or German-Americans” which could have been used to destroy railroad structures in the hopes of delaying the movement of American troops and supplies. On June 21st, the Cornwall-on-Hudson Press ran an article encouraging its citizens to “Enlist with the Men You Know” and that the men of Company F “has been with us long enough that our people have become acquainted with them, and know them to be a thoroughly fine lot of men from the captain to the “Rookies”. A Cornwall young man who joins their ranks does not need to feel that he is going among strangers but among friends” [4].

One member of the 71st who made an acquaintance with a Washingtonville citizen was Lieutenant Hubert Vincent Davis of Rutherford, New Jersey. Hubert enlisted in Company K of the 71st in March, 1917 at the age of 18, and was sent to Middletown the following month. According to his memoirs; written when he was 84, he states:

“Because of fear of sabotage to transportation and water supply the regiment was assigned to guard duty on bridges and water mains supplying N.Y. City. The first battalion of the 71st Regiment set up headquarters in Middletown, N.Y. The first squad of Company K, of which I was a member, was assigned to guard a railroad bridge. “Standing Guard” meant each of us had to walk our post four hours, after which we got eight hours off duty.” [5]

Shortly after arriving in Middletown, Davis began a friendship with Ethel Hudson of Washingtonville. He makes no mention of her in his memoirs, so it is unclear how they met, but Ethel’s descendants have described her as a “social butterfly” and one who kept correspondence with many possible suitors during the war. One surviving letter from Hubert to Ethel; written while he was stationed in France, shows he had been to Washingtonville to visit:

“While at a hospital in France I met a lot of nurses who know Miss Owen of W’ville. If I remember rightly, Miss Owen is the daughter of the gentleman who owns that general store on the corner of the square” [6]

By August 1917, the regiment was relieved of its duties by the provisional New York Guard; a home defense corps, and returned to Van Cortlandt Park in New York City, and then for training in Camp Wadsworth South Carolina. Hubert Davis would eventually rise from Private to 1st Lieutenant, and served with distinction overseas; all the while keeping a correspondence with Ethel Hudson. Susan Brown would marry fellow soldier David Wright Hudson, although his regiment was never stationed on the Brown Farm. As for the 71st, the regiment was dispersed to the 105th, and 106th Regiments of the 27th “New York” Division, which played a crucial role in spearheading the assault on the Hindenburg Line in October 1918. The railroad trestles and bridges the 71st was entrusted to defend were never destroyed [7]. As for the citizens of Blooming Grove, they would never forget those few months in 1917 when the war came home.

SOURCES

- Letter: Elsa S. Gerow to David Wright Hudson, December, 1917

- Letter: Emily Hudson Wright to David Wright Hudson, 1917

- King, Gilbert. “Sabotage in New York Harbor.” Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian Institution, November 1, 2011. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/sabotage-in-new-york-harbor-123968672/.

- Sutliffe, Robert. Seventy-First New York in the World War. New York: J. J. Little & Ives co., 1922.

- FamilySearch – Episodes in the Life of Hubert Vincent Davis, Sr.

- Letter: Hubert Vincent Davis to Ethel Hudson, December 14, 1918

- 105th NY Infantry Regiment during World War One – NY Military Museum and Veterans Research Center. Department of Military and Naval Affairs, December 8, 2009. https://dmna.ny.gov/historic/reghist/wwi/infantry/105thInf/105thInfMain.htm.