Throwback Thursday, May 4, 2023: The Akers Family Collection

On this installment of our Throwback Thursday blog, our local history librarian shares a collection of letters from the Moffat Library’s Akers Family Collection to shed some light on a theory that throws the authorship of William Shakespeare’s works into question, and local historian Dwight L. Akers’ obsession to find the truth!

William Shakespeare (1564-1616), was born around April 23, 1564 in Stratford, a small town located in the county of Warwickshire, in England’s “West Midlands” to Mary Arden, the daughter of a local landowner, and John Shakespeare, a glove maker and farm trader. Despite moving up the social ranks to become the Mayor of Stratford in 1569, William’s father would encounter financial troubles which kept the family from achieving notoriety beyond their small village. Although no documentation of William’s school years survive, scholars note that his literary ability is a mark of a well-rounded education. Although William would eventually make his mark as a noted playwright and author, his early years, and those specifically between 1585 and 1592, have been subject to controversy as there is no documentation that notes his occupation or location during this time.

Despite going onto become one of the world’s best known poets and playwrights, authoring such works as The Two Gentlemen of Verona (1591) The Taming of the Shrew (1594), and Romeo & Juliet (1596), as well as countless sonnets, William Shakespeare’s “Lost Years” from 1585 to 1592, as well as his early education have captured the imaginations of skeptics and scholars for generations. Beginning in the 19th century, various commenters proposed that William Shakespeare did not write works that were attributed to him, or did not exist at all. Some claiming that he was a corporate entity, a pen-name for a group of writers who published works as him, or specific individuals such as Edward de Vere or Francis Bacon. The collective term for sceptics who deny William Shakespeare’s identity or authorship is “Anti-Stratfordians.”

Because Shakesepeare was not born of the nobility, contemporary biographical documents that would have traced lineage do not survive compared to other well-known authors of his time. The fact that there are no authenticated manuscripts written in his hand, provides Anti-Stratfordians with additional fodder to support their theories.

Anti-Stratfordians also assert the claim that Shakespeare’s education, well-rounded and advanced as it was, is not enough to explain the genius of his writings. Despite the fact that there is only circumstantial evidence that leads one to doubt the authorship of Shakespeare’s works, new theories involving supposed biographical references in Shakespeare’s plays to one or other alternatives continue to fuel this controversial theory.

In 1952, Dorothy (b.1890) and Charlton Greenwood Ogburn (1882-1962) published The Star of England, in which they contested that the authorship of Shakespeare’s plays was attributed to Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford. This claim, known as the “Oxfordian Theory”, is based on the fact that Edward was not only born of noble birth, which afforded him a high level of education as well as knowledge of court protocol, as noted in many of Shakespeare’s works, but also a playwright and poet who also led a theatrical troupe known as “Oxford’s Men”. Their son Charlton Ogburn Jr. would later carry on this legacy in the 1970s when he was elected president of the Shakespeare Oxford Society, and began publicizing and hosting mock trials, media debates, media appearances and internet forums to promote this theory and recruit members. One local scholar who considered themselves a “former disciple of the Oxford School” was local historian and author Dwight L. Akers (1886-1968).

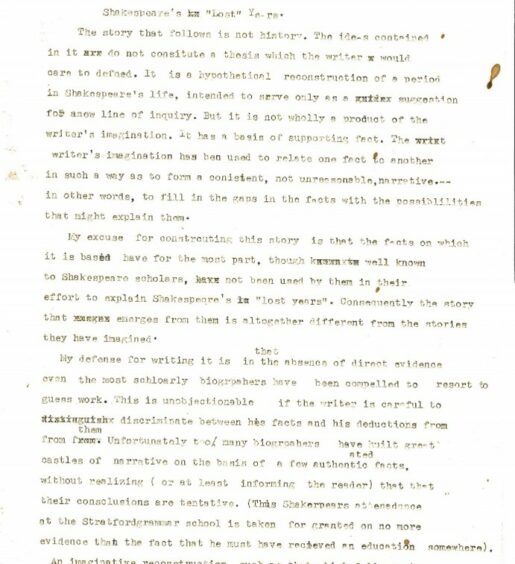

Around the time the Ogburns published The Star of England, Akers, known for his short stories and works of historical fiction and non-fiction, wrote an essay entitled Shakespeare’s “Lost” Years , in which he states that:

(The story that follows is not history. The ideas contained in it do not constitute a thesis which the writer would care to def[e]nd. It is a hypothetical reconstruction of a period in Shakespeare’s life, intended to serve only as a suggestion for a new line of inquiry).

In this work, Akers attempts to piece together the life of William Shakespeare during the period between the end of his formal schooling and his arrival in London, while asserting that Shakespeare’s education in the theater and court protocol were attributed to Alice Spencer, the wife of Ferdinando Stanley, Lord Strange. Strange and his “Company of Players” have been assumed by many to have employed Shakespeare, however this fact is in dispute due to lack of evidence. In addition to his own research into Shakespeare’s genius, Akers also reached out to the Folger Shakespeare Library, the premier institution on researching Shakespeare and his works, John Leslie Hotson (1897-1992), an Elizabethan literary scholar best known for his 1925 work The Death of Christopher Marlowe, and Dorothy and Charlton Ogburn themselves. In so doing, Akers amassed a collection of notes and correspondence from several noted Shakespeare scholars, as well as his detractors.

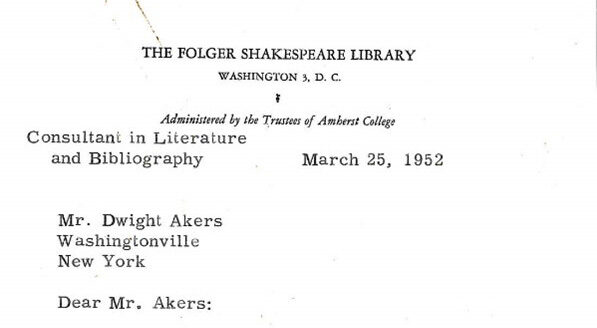

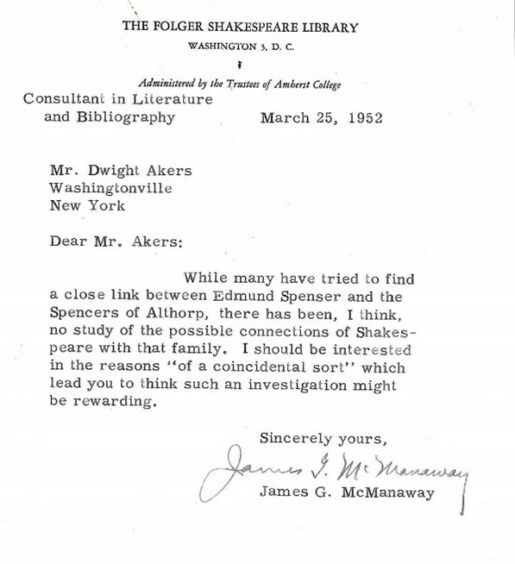

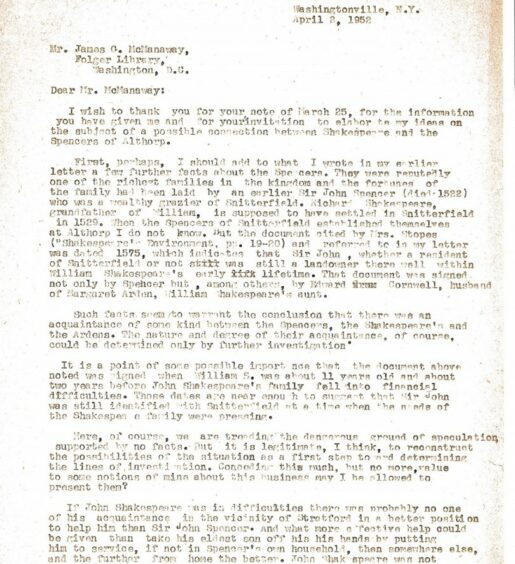

The correspondence Akers kept with these noted individuals provides an entertaining and informative glimpse into the life of someone whose intellectual curiosity could not be easily satiated. In a March 25, 1952 response for a request from Akers in regards to a link between contemporary Elizabethan playwright Edmund Spenser and Alice Spencer, James G. McManaway, Consultant in Literature and Bibliography at the Folger Shakespeare Library wrote:

While many have tried to find a close link between Edmund Spenser and the Spencers of Althorp, there has been, I think, no study of the possible connections of Shakespeare with that family. I should be interested in the reasons “of a coincidental sort” which lead you to think such an investigation might be rewarding.

On April 2nd Akers explained his previous request (as of this time not found in our collection), that:

First, perhaps, I should add to what I wrote in my earlier letter a few further facts about the Specners. They were reputedly one of the richest families in the kingdom and the fortunes of the famly had been laid by an earlier Sir John Spencer (died 1522) who was a wealthy grazier of Snitterfield. Richard Shakespeare, grandfather of William, is supposed to have settled in Snitterfield at Althorp

in 1529. When the Spencers of Snitterfield established themselves at Althorp I do not know. But the document cited by Mrs. Stopes (“Shakespeare’s Environment, pp. 19-20) and referred to in my letter was dated 1575, which indicates that Sir John, whether a resident of Snitterfield or not was still a landowner there well within William Shakespeare’s early lifetime. That document was signed not only by Spencer but, among others, by Edward Cornwell, husband of Margaret Arden, William Shakespeare’s aunt”.

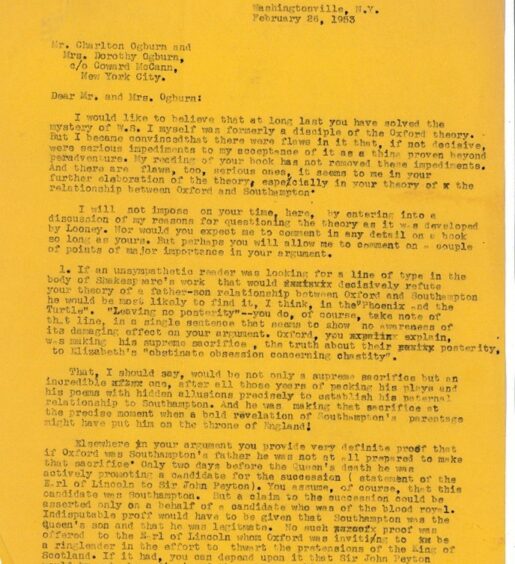

A reply from McManaway to this letter has yet to be found, but Akers continued his line of inquiry and on February 26, 1953 wrote Charlton and Dorothy Ogburn a four-page critique following the publication of The Star of England:

I myself was formerly a disciple of the Oxford Theory. But I became convinced that there were flaws in it that if not decisive were serious impediments to my acceptance of it as a thing proven beyond peradventure. My reading of your book has not removed these impediments. And there are flaws too serious ones, it seems to me in your further elaboration of the theory, especially in your theory of the relationship between Oxford and Southampton.

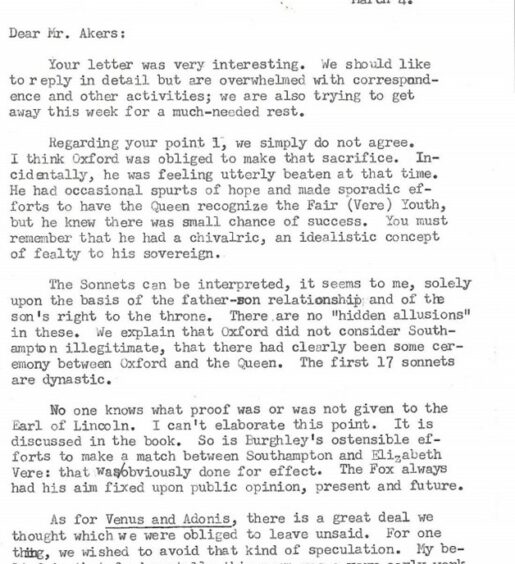

The following week, on March 4, 1953, Akers received a two-page response from Dorothy Ogburn who admitted: “We should like to replay in detail but are overwhelmed with correspondence and other activities; we are also trying to get away this week for a much-needed rest” but attempted to respond to his comments as best she could.

In the final paragraph she stated that:

It seems to me that you rather arbitrarily overlook certain points we make. But this is natural, since you do not agree with our central theses. I am sorry. To me this story is the greatest, the most dramatic, of the Western world. Although the obscurantist English Professors, the Stratford interests and their counterparts and colleagues here will fight to the death for their mythical genius, a number of scholars and distinguished lawyers have assured us that we have proved our case.

Thank you for writing.

Although Akers never intended to go beyond a theory to account for Shakespeare’s “Lost Years” as well as secondary education and early interest in theater, he amassed a substantial collection research notes, as well as letters from his contemporaries who attempted to answer his questions the best they could. Our library is honored to be the custodian of these and other materials related to Dwight and Emily Akers, who we hope to display, share and make available as we continue to process their personal records.

SOURCES

Akers, Dwight L. Dwight L. Akers to James G. McManaway, April 2, 1952.

Letter. From Moffat Library of Washingtonville. Akers Family Collection.

Akers, Dwight L. Dwight L. Akers to Charlton & Dorothy Ogburn, February 26, 1953. Letter. From Moffat Library of Washingtonville. Akers Family Collection.

Akers, Dwight L. Shakespeare’s Lost Years. Manuscript. From Moffat Library of Washingtonville. Akers Family Collection.

Decker, James M. “The History of the Authorship Controversy.” In Baker, William, and Kenneth Womack, The Facts On File Companion to Shakespeare, 139-148. Facts On File Library of World Literature. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Facts on File, 2012. Gale eBooks (accessed April 20, 2023). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX2025400020/GVRL?u=nysl_se_moffat&sid=bookmark-GVRL&xid=a4f0db64.

McManaway, James G. James G. McManaway to Dwight L. Akers, March 25, 1952. Letter. From Moffat Library of Washingtonville. Akers Family Collection.

Ogburn, Dorothy. Dorothy Ogburn to Dwight L. Akers, March 4, 1953. Letter. From Moffat Library of Washingtonville. Akers Family Collection.

“William Shakespeare.” In Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2nd ed., 142-145. Vol. 14. Detroit, MI: Gale, 2004. Gale eBooks (accessed April 20, 2023). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX3404705894/GVRL?u=nysl_se_moffat&sid=bookmark-GVRL&xid=1754f2e2.