Blooming Grove and the First World War: Part 5

As thousands of soldiers were being exposed to the horrors of war overseas, an enemy was ravaging millions of people on a global scale. The Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919, also referred to as “The Spanish Flu” is considered to be one of the most devastating outbreaks of the 20th century [1]. Although its origins are unknown, it was referred to as the “Spanish Flu” due to neutral Spain’s lax censorship laws, which resulted in reported flu deaths being broadcast to other nations otherwise occupied with the First World War [2]. The pandemic struck in three separate waves, a mild wave spread across Europe beginning in March 1918, with more lethal waves arriving between August and October of that year, and a third wave in the winter of 1919. In the United States, these waves corresponded to rapid mobilization of troops following the declaration of war, along with the celebration of their return following hostilities [3]. By the time Influenza Type A, Sub-type H1N1 had run its course, 500 million world-wide cases had been reported, and between 25 and 50 million people were dead, including 650,000 in the United States, and 26,500 in New York State [4].

Lack of a vaccine, and antibiotics to treat this outbreak left officials with few non-medicinal options, however New York State Health Commissioner Hermann M. Biggs, M.D. took immediate charge of the situation. He requested having the New York State Department of health issue warnings against spitting, coughing without covering the mouth, and other unsanitary practices. Guidelines for reducing the spread of the disease were also put in place, such as closing large public gatherings, cinemas, and schools as well as early detection, and isolation practices [4].

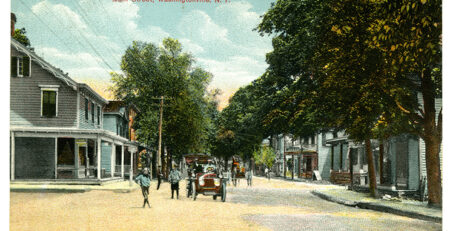

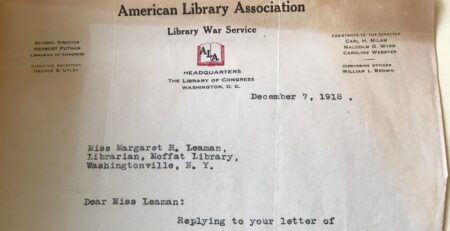

The affects of the flu pandemic in our area are so far unknown, however we do know that between October 1st and December 31 1918, the Department of Health for New York State reported a total of 7,930 cases of influenza in Orange County alone. The library also has minute books of the local chapter of the American Red Cross which cover this period, which require further study. We also know at this time Washingtonville was going through a severe bout of dysentery, a gastrointestinal infection, caused by polluted drinking water [5]. According to Hermann M. Biggs, local officials failed to take proper measures following earlier surveys of the village water supply in 1909 and 1915, resulting in the contamination of the a tributary of the Moodna Creek following runoff caused by a thaw in February, compounded with close proximity of several farms in relation to the village water supply. This resulted in “at least 30 cases of dysentery…and probably a great many more which did not come to the attention of physicians at the time” [5].

An extract of a letter from local resident Marcus C. Sears, written to David Wright Hudson, who was currently serving overseas also gives us a glimpse into what it was like to live through the 1918-1919 Flu Pandemic. Dated February 26, 1919, Sears notes that he was infected in December 1918, meaning this was the third wave of the H1N1 flu. It also mentions the affects the war has had on the small community of just over 2,000 people.

“Blooming Grove, N.Y. Feb 26, 1919.

Dear David,

I have been very glad to hear through to hear that you got through the fighting without getting killed or badly wounded. I expect you, like all the rest we hear about want to get home. You may be sure we will all be glad to see you. But there is a good deal our army has got to do over there yet & some body has got to stay & do it. I have thought about you very often & thought I would write but did not get at it. Probably you wonder why I write at this late date. Well it is partly because I have been shut in with the influenza & pneumonia since Christmas & have been thinking more about friends & my old group of boys who used to meet so often with Mr. Wilcox & me. I have been down stairs for a week but have not been out doors for 2 months. A great many have been sick about here from the influenza & many of the younger people have died. The influenza has taken many many more from this community than the war and the toll throughout the nation has been greater than the American Casualties in France. I am surprised how few of the men from were killed or wounded so far as I have heard. The news of Chadwick [Gerow]’s death cast a shadow over our little community. This comes home to me more as the time passes. But Chadwick died bravely with an untarnished record. He kept the faith & fought a good fight & he has his reward.

I can not tell you much news as I am not hearing much now. Our Y.M.C.A. work has been at a stand still during the

war. All the available men for secretaries went into the war work and we were obliged to go without one when Mr. Wilcox went away. I hope we can soon get going soon. I don’t know whether this will reach you before you start for home or not. It comes from one who wishes you a safe return with all his heart. May God bless & keep you.

Yours sincerely

Marcus C. Sears

P.S. I do not know your address so I send this to

your mother to address.

M.C.S.”

By the time of the third wave in the spring of 1919, it was believed the more lethal strains of the virus had run their course and reported deaths began to decline [3]. Although the 1918 H1N1 influenza virus has been synthesized in order to better evaluate current and future health interventions, and antivirals are available to treat it, scientists and medical experts continue to investigate, monitor and mitigate the affects of future outbreaks, as they did in 1930, 1957, 1968, 2009, and most recently in 2020.

SOURCES

- Britannica Academic, s.v. “Influenza pandemic of 1918–19,” accessed April 22, 2020, https://academic.eb.com/levels/collegiate/article/influenza-pandemic-of-191819/2537.

- Wills, Matthew. “The Flu Pandemic of 1918, as Reported in 1918.” JSTOR Daily. JSTOR, January 15, 2018. https://daily.jstor.org/the-flu-pandemic-of-1918-as-reported-in-1918/.

- “History of 1918 Flu Pandemic.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, March 21, 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-commemoration/1918-pandemic-history.htm.

- Escuyer, Kay L, Meghan E Fuschino, and Kirsten St George. “New York State Emergency Preparedness and Response to Influenza Pandemics 1918-2018.” Tropical medicine and infectious disease. MDPI, October 30, 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6958434/#B3-tropicalmed-04-00132.

- Thirty-Ninth Annual Report, 2 Thirty-Ninth Annual Report § (1919).